In this short series, Dominic Dalglish responds to three appraisals of the Imagining the Divine exhibition from some of the UK’s leading scholars. In this piece, we turn to the comments of Mary Beard on ‘blobs’.

In January we were lucky enough to be joined by Mary Beard and Neil MacGregor, to hear their takes on Imagining the Divine and some of the questions raised by the exhibition.

Inevitably, alongside praise, there was some pointed critique! We would expect nothing less. In the spirit of openness, I want to draw attention to what Mary and Neil had to say (and to one of the audience members questions), and to try and offer some responses.

This could be taken as a shameless attempt to get one over on our esteemed critics. However, I hope that by responding to what are very interesting observations, it will serve to open up some of the different ways that we can think about the objects and images in the exhibition, and hopefully also draw your attention towards some of the fabulous things that one can unfortunately miss in such a large and varied exhibition.

In this first piece, we look at what Mary Beard had to say.

The first two criticisms from Mary and Neil came in response to a question by Mallica Kumbera-Landrus about the aspects of religion that we cannot expect to address in an exhibition (c.38:55).

Mary was first to respond – you can watch this here, but I have paraphrased below:

Mary:

The exhibition inevitably shows you the Art with a capital A of religion. Don’t go to the exhibition expecting to see any planks… the exhibition inevitably excludes those bits of religious imagery that don’t fit into our view of what imagery worth being in a museum means.

I would love to have an exhibition… that was all planks and blobs!

A little later on she continues…

Mary:

It makes classical religion seem much less weird than it really was, by getting it and putting it in cases and having it as sculpture that we should admire…

We have here a very calm view of religion to which one could take a child, it doesn’t have an X-rating, there’s no godlets sleeping with goats, no incest, no nothing. A very suburban view of Roman religion!

To summarise, I’m going to refer to these as ‘blobs’ – forms of gods that are not ‘beautiful’ in the sense that they look really like humans. Bits of wood, carved crudely or sometimes not at all, and types of stone that quite literally look like blobs, but were believed in some way to be the god.

The point Mary’s making is a very good one – museums as institutions, particularly when it comes to the art of the ancient world, were built upon the donations and bequests of the great collectors of the 17th and 18th centuries. The Townley collection at the British Museum, and of course those of Lord Elgin, and the Randolph collection in the Ashmolean, act as the bedrocks of what we present to the public. What they are, are products of connoisseurship – the mass accumulation of ancient art that was considered valuable, in no small part because of its aesthetic value. The grand tours that British (and French, German, Danish, Dutch) gentry embarked upon were often not complete without an ornament for the garden – a talking point, perhaps, but certainly something that could immediately communicate ones education and status as a travelled and informed individual. Blobs just weren’t that welcome.

It is also a problem of survival. Many of the weird and wonderful elements of ancient religion (to us at least) appear to have been made out of ephemeral or highly degradable material. Planks just haven’t survived, and nor have countless dedications to gods made by those with less-means, in clay, wood, fabrics, or even food-stuffs. Today, those bits and pieces that have are thankfully highly valued, but they are incredibly rare.

Apart from these excuses – for that is what they are – I’d like to offer two responses in relation to Imagining the Divine.

The first is that the exhibition has got blobs, but that you have to look for them. On the left in the image above, you can see a stone container. This object, and others like it, were used as reliquaries to hold precious items such as coins and beads, and particularly relics associated with the Buddha and important Bodhisattvas – pieces of bone in this instance. In this case, the divine is literally present – what was being protected by this container, were remnants of a transcendent being worthy of adoration.

The blobs of which Mary was speaking, are some of the ‘un-lifelike’ representations of divinity that we know to have existed in the ancient world. Here, of course, we have only a part of a figure of veneration, and something that was believed to have derived from its person. But the step that one must take, in terms of investing in these objects as the divine is not so very different.

Above is a model stupa. It was in such objects and monuments, that reliquaries were placed. Stupas were an important part of Buddhist religious practice – circumambulation of these objects and monuments was part and parcel of worship. The reliquary, therefore, should be understood within this context, but we should also reflect on the stupa itself.

This type of monument has been variously understood – there is no single interpretation of the significance of its form. But we know that for some, at least, the stupa represented the seated Buddha himself: his legs the steps, four in total; his body the trunk of the stupa; his head the structure above. If we look beyond the decoration of this wonderful object, replete with numerous representations of the Buddha in the form of a man, we can also see one of the blobs that Mary was after.

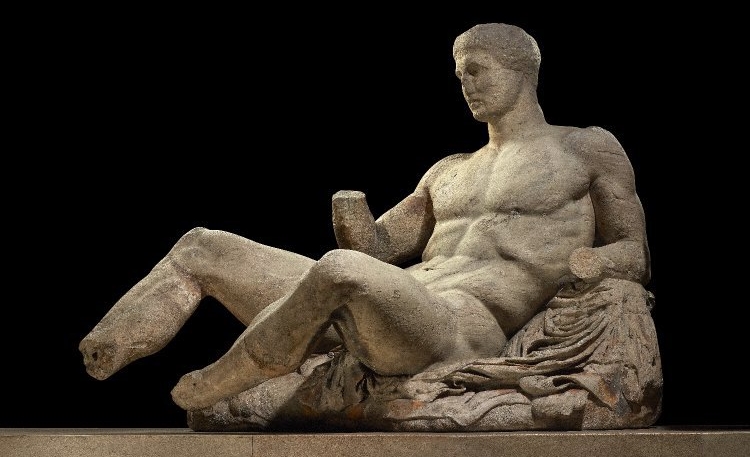

The second response surrounds one of the objectives of the exhibition, and the work that the Empires of Faith project has embarked on. As I suggested, the collection of antiquities that now form a large part of prominent museum collections focussed on their aesthetic value – the two objects here (above and below), which both feature in the exhibition, can readily be described as ‘beautiful’ – as works of art, with a capital A as Mary put it.

What they are far less often described as is ‘religious’ – they are not considered for what they might communicate about ancient religion beyond acting as representations of gods that we know about from what we are told in texts. So one of our objectives, in fact, in putting on this exhibition – particularly in the section on the ancient Mediterranean – was to try and reclaim these as religious objects. To think about how they were used, and what they can communicate about understandings of the gods they depict.

So – a big thank you to Mary Beard for raising a very interesting issue. Keep your eyes peeled for blobs in the exhibition and look beyond ‘beauty’ in search of something more, but also let us know what you think.

To follow soon, Neil MacGregor on BBQs and exhibitions.

===

Author: Dominic Dalglish

Thank you to TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities) for supporting the event, without whom it would not have been possible.